Why have women been historically kept out of church leadership

A Historical Response to the Claim That Tradition Justifies Excluding Women from Church Leadership

For much of church history, the exclusion of women from leadership has been explained as a matter of cherry-picked doctrine. As though the answer lies neatly inside a handful of verses—clear, settled, unavoidable.

But history rarely works that way.

When you step back from proof texts and look at how Christianity actually developed over time—who held power, what pressures shaped belief, and what the church was being asked to do in the world—the question shifts. The issue is not whether women were capable of leadership. It is what kinds of leadership the institutional church came to require, and which forms of moral authority it found threatening.

The earliest Jesus communities were not modern egalitarian collectives, nor were they free from the social hierarchies of their time. But they were decentralized and largely household-based. Leadership emerged locally, shaped by relationship, patronage, and recognized spiritual maturity rather than by rigid office or enforceable hierarchy. In those conditions, women’s leadership was visible and functional—not because the culture was unusually progressive, but because authority had not yet hardened into centralized control.

“Conscience-based authority, once released into public life, does not easily recede.”

We can see an example of patronage clearly in the example of Phoebe, whom Paul commends in his letter to the Romans not only as a deacon of the church at Cenchreae, but as a benefactor—someone who materially supported and protected the community, including Paul himself. Phoebe was entrusted with carrying Paul’s letter to Rome, a role that required authority, trust, and interpretive responsibility. Her leadership did not come from a formal title imposed from above, but from the concrete work of sustaining the church and the moral authority that flowed from it.

This sort of relational structure changed as Christianity became aligned with empire.

Beginning in the fourth century, especially after the reign of Constantine, the church’s social function shifted. Christianity moved from a marginal, formative way of life into an institution tasked with stabilizing a vast political order. Councils standardized belief. Authority consolidated. Orthodoxy became something that could be enforced rather than discerned.

Empire requires hierarchy.

Empire requires obedience.

Empire requires clear lines of authority.

Scripture was increasingly read through those needs.

Texts that supported submission, order, and rule were emphasized. Isolated passages were elevated into timeless mandates, often detached from their historical and cultural context. Apocalyptic language was reinterpreted as cosmic enforcement rather than pastoral warning. Over time, the Bible functioned less as a tool of moral formation and more as a document that could legitimize power.

A heart-centered, Jesus-centered reading does not serve that purpose well.

Reading the Gospels closely—through the life and teachings of Jesus rather than abstracted authority—draws attention to mercy, humility, repentance, and love of neighbor. It locates moral authority in fruit rather than office, in faithfulness rather than control. That kind of reading resists domination. It cannot easily be weaponized. And historically, it has often been women who preserved and enacted it most visibly.

This is not because women are inherently more virtuous, but because their exclusion from formal power often kept their moral authority from being fully absorbed into institutional hierarchy. Jesus himself warned how easily accumulated power resists transformation—how difficult it is for those who hold it securely to pass through the narrow demands of the kingdom 🐪🪡 Authority that cannot be possessed or controlled has a way of remaining spiritually agile, capable of critique rather than capture.

When leadership is grounded in conscience rather than coercion, it resists standardization and becomes difficult to manage from the top down.

What’s striking is what happens whenever those constraints loosen.

In the nineteenth century, some of the most significant reform movements in the United States—abolition, temperance, prison reform, and women’s suffrage—were led by Christian women. These were not secular projects borrowing religious language. They were explicitly grounded in Christian conscience, biblical literacy, and moral responsibility.

Many of these women came from traditions that already trusted women with spiritual authority, particularly the Society of Friends. From their beginnings, Quakers recognized women as ministers, elders, and public speakers. Moral authority was discerned communally rather than imposed hierarchically, and obedience to conscience was treated as obedience to God.

That formation mattered.

Women shaped by these communities were already trained to speak publicly, reason theologically, and challenge unjust authority in religious terms. They did not need to invent a new moral language to enter public life; they extended the one they had already been practicing.

Figures such as Lucretia Mott, Sojourner Truth, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton did not abandon Christianity in order to lead. They acted because of it. Their authority did not rest on office or institutional permission, but on moral clarity, biblical literacy, and an insistence that Christian faith be measured by its fruits rather than its precedents. They appealed not to disruption for its own sake, but to the contradiction between professed belief and lived reality

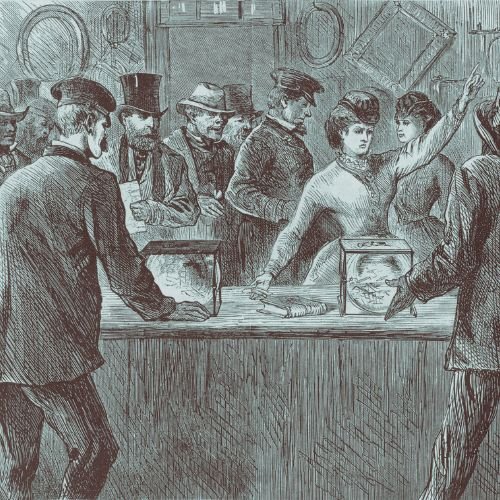

Illustration from the 19th century depicting women participating in civic life during the suffrage movement.

That lineage did not end with the nineteenth century. It carried forward into the civil rights movement of the twentieth, where figures such as Fannie Lou Hamer drew on the same moral framework—scripture, conscience, testimony, and an unflinching exposure of hypocrisy. Hamer’s leadership did not come from institutional rank, but from lived truth, moral courage, and a refusal to separate faith from justice.

Fannie Lou Hamer speaking during the civil rights movement, embodying a tradition of faith-rooted moral authority and public witness.

Her authority, like that of those before her, was persuasive rather than coercive, grounded in witness rather than controlThe pattern extends beyond a single movement or tradition. Later leaders such as Dolores Huerta carried forward the same ethic: organizing rooted in moral conviction, dignity, and the insistence that those long excluded from power could nevertheless speak with authority about the common good. These movements did not merely win reforms; they reshaped the moral imagination of the nation. The changes they initiated did not conclude with their lifetimes. They continue to unfold, because conscience-based authority, once released into public life, does not easily recede.

What these movements established was not only legal reform, but a durable moral logic: that conscience can stand in judgment over law, that excluded voices can speak moral truth to power, and that faith is meant to reform the world rather than merely stabilize it.

This continuity helps explain why such movements—and the women who led them—have remained unsettling to entrenched hierarchies. Once moral authority is no longer confined to office, gender, or status, it cannot easily be reclaimed. A tradition that teaches ordinary people—women, formerly enslaved people, the socially excluded—to speak publicly in the name of conscience permanently alters the terms of power.

From this perspective, the historical resistance to women’s leadership in the church was never primarily about biblical fidelity. It was about manageability. A church aligned with hierarchy learned to distrust voices that emphasized mercy over dominance, discernment over decree, and relationship over rank.

Women were not excluded because they lacked authority. They were excluded because they represented a form of authority that could not be fully controlled.

And that—more than any verse or appeal to tradition—explains the long resistance to their leadership, and why its effects continue to echo.